Our Annual Christmas Book Recommendations

Our apologies - We are a little late with our annual list, but hopefully you will find our recommendations both interesting and fun!

Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn by Christopher Cox (Simon & Schuster, 640 pages, 2024)

Growing up, Woodrow Wilson was lionized in the classroom, held up as a paradigm of enlightened leadership and vision. As the former President of Princeton University and New Jersey Governor, he was the man who helped negotiate the Armistice of World War I, pushed for the League of Nations (which, while failing in that form, led to the establishment of the United Nations decades later), and established the Federal Reserve. What we were never taught was that he was also a determined southern racist who advanced Jim Crow laws while doing all he could to deny women the right to vote - but who then flipped at the last moment to support women’s right to vote in return for further advancing Jim Crow laws. Cox, a former Member of Congress and Chair of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, has done an extraordinary amount of research in writing this book. I found it hard to put down.

Private Finance, Public Power: A History of Bank Supervision in America by Peter Conti-Brown and Sean Vanatta. (Princeton University Press, 424 pages, 2025)

On first blush, you may think this is not going to be the most scintillating of topics. But the authors bring to life the critical importance and historical impact of what keeps America’s finance machine running - or, at times, plays a role in crashing. Banks in America are private institutions with private shareholders, boards of directors, profit motives, customers, and competitors. And yet the public, Washington, and state policymakers play a key role in deciding which risks are taken, as well as how, when, and to what end. Conti-Brown and Vanatta examine how the US has managed financial risk and how it has evolved to become engaged in more social policy issues, such as monitoring racial discrimination, managing financial concentration, and, more recently and controversially, climate change. The book weaves in a large cast of historical characters who have played outsized roles in all of this, through the best of times, financial panics, and scandals.

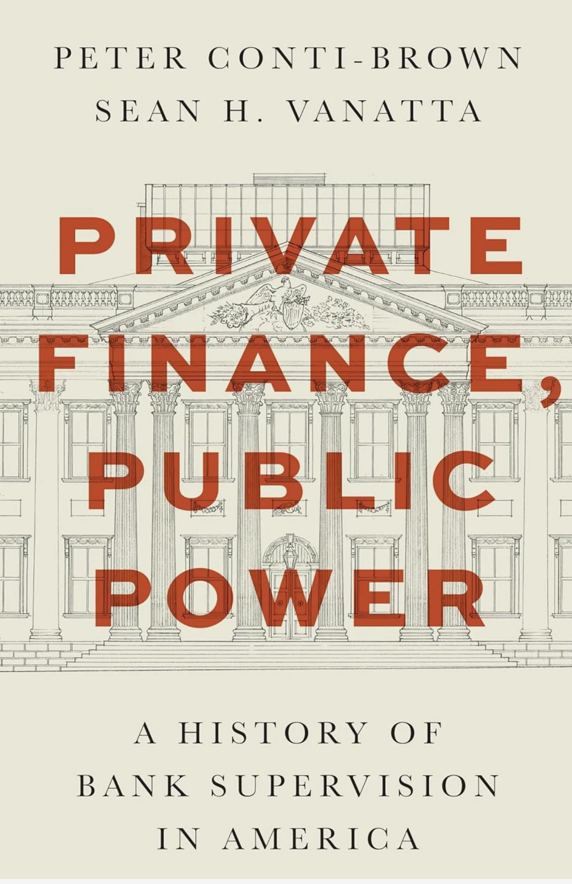

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan, translated by Jack Hargreaves (Astra House, 336 pages, 2025)

A best-seller in China in 2023, Hu Anyan recounts his brutal, low-paying work as a parcel delivery worker with very little hope for a better life ahead. Straightforward and candid, Hu’s writing conveys the cultural shift in China where young people question the traditional work-for-success model and reflecting a society grappling with rapid economic change - more than hinting at the intense struggles inside China today as it grapples with internal political and economic challenges the West normally cannot see.

Mexico: A 500 Year History by Paul Gillingham (Atlantic Monthly Press, 752 pages, 2025)

Mexico has always been of special interest to me, and I have enjoyed reading about its history. When Gillingham came out with this mammoth new history - 752 pages - I was a bit intimidated and wondered if I would learn anything new. Happily, this is a brilliant, elegantly written book, and the author has done tremendous research. In short, I learned a lot. As the US begins a slow and likely arduous new round of trade negotiations with Mexico, it’s an essential contribution to understanding the enormous changes and upheaval Mexico has experienced over the last 500 years and why a lot of the changes still to come are going to be incredibly important not just there but to the US and the rest of the Western Hemisphere.

The French Revolution: A Political History by John Harman (Yale University Press, 384 pages, 2025)

We all know the basics of the French Revolution: Let them eat cake, uprisings in the streets, and off with their heads. But it was much more than that as this excellent history by John Hartman makes clear - and its ramifications are still being felt today in various ways. How and why did the ancien régime blow apart so fast and so violently? A great read.

1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History and How it Shattered a Nation by Andrew Ross Sorkin (Viking Press, 592 pages, 2025)

Sorkin’s history of the fateful stock market crash in 1929 is a fascinating and vivid read of how what was thought to be an unstoppable stock market spectacularly crashed, sending the US into a depression and forever changing the nation. Sorkin has done some fabulous research here, and in an age when we are debating crypto and AI bubbles, there are many lessons to be gleaned.

King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution: A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation by Scott Anderson (Doubleday Press, 512 pages, 2025)

Scott Anderson (Doubleday, 512 pp., $35, Aug. 5)

President Trump’s recent bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities reminds us that the relationship between modern-day Iran and the US is a long and brutal one. Anderson takes readers back to when the troubles began in 1979, when the Shah of Iran was toppled. A great history and reminder of just how complicated and deadly the relationship has become and likely to remain for the foreseeable future.

Eclipsing the West: China, India and the Forging of a New World by Vince Cable (Manchester University Press, 352 pages, 2025)

Cable has an extensive and highly impressive career: Beginning as a development economist, chief economist at Royal Dutch Shell, member of the UK Parliament, Leader of the Liberal Democrat Party, and UK Minister for Business, Innovation, and Skills under Prime Minister David Cameron, and a minister in the UK coalition government under David Cameron. He writes a fascinating analysis of the increasingly tense relationship between the West and Asia, specifically China and India. Cable sees three possible future scenarios playing out: A democratic “Global West” confronting autocratic adversaries, led by a failing China, with India joining the democracies; or a multi-polar world, with a rising China and a rising India and no hegemon; or a multilateral world, with a reformed, but functional, postwar order and, again, no hegemon. Smartly written, it leaves the reader plenty to ponder about how all this will play out.